The final drop: Women are still underrepresented as college presidents

Women CEOs are in charge of 10% of Fortune 500 companies, according to Fortune magazine. Comparatively, the figures of 20% of Central Massachusetts colleges and 39% of Massachusetts colleges being run by women seems quite impressive in the strive for equality.

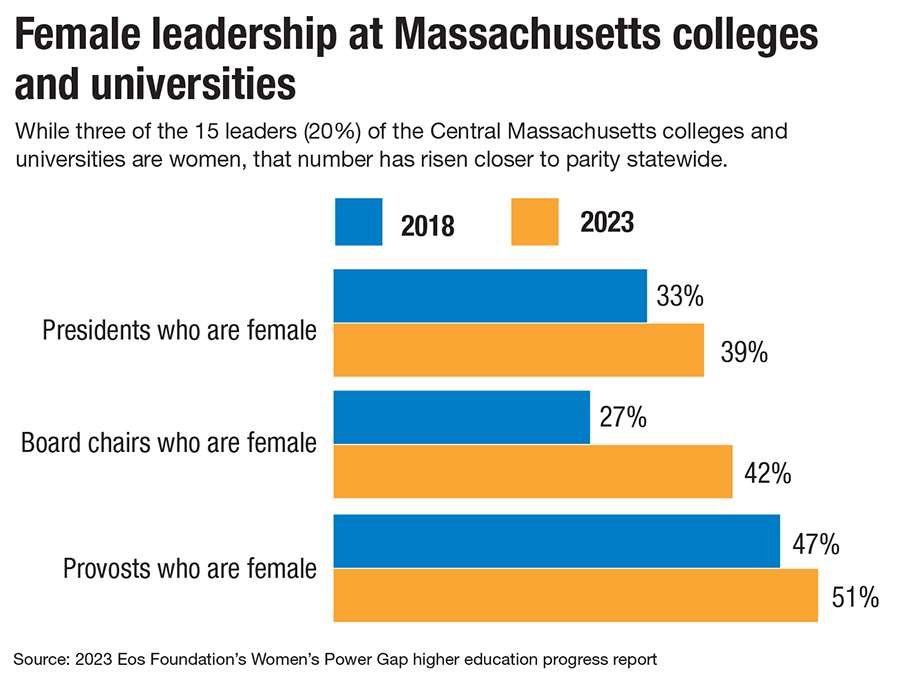

Yet, despite the improvements over the past five years, during which the statewide figure has increased from 33%, according to the Eos Foundation’s Women’s Power Gap higher education progress report, there remains a disconnect between the talent pool vying for the top spot in college leadership and the amount of women who actually make it there. That discrepancy has impacts on students and the future of innovation in higher education.

“If you don't see a female president, it's hard to imagine some day you will become one,” said Grace Wang, president of Worcester Polytechnic Institute. “The talent is there, but do you feel empowered and inspired?”

A slim majority of college and university provosts across Massachusetts are women, making up 51% of the often second-in-command role in higher education, according to the report from the Eos, a Harwich Port-based private foundation. This year was the first time this provost figure reached parity, after increasing 4 percentage points since the foundation’s 2018 report.

“So many women are going into higher education, and there's such a strong talent pool,” said Silbert.

The gap between percentage of women as provosts and percentage of women as presidents is indicative of a problem in the selection process for presidents, said Andrea Silbert, Eos president.

“If you have women as 50% of provosts, I would expect to see women as 50% of presidents. Women are in the applicant pool,” said Silbert. “We should already be there.”

Three out of 15

Women make up a majority of student bodies across Massachusetts colleges and universities, at 58% in 2023. The talent pool of women interested in becoming and qualified to be college presidents is there, said Silbert. Still, higher education isn’t immune to the so-called final drop, the corporate term for the gap between the percentage of women leaders who make up C-suites and the relatively smaller portion who are CEOs.

Some 26 higher education institutions in the state have never had a woman president, including five in Central Massachusetts: Assumption University, Clark University, College of the Holy Cross, Fitchburg State University, and UMass Chan Medical School, according to the report.

Wang is the second female president at WPI, having taken over leadership of the school in April from Laurie Leshin, who became the first woman president of the 158-year-old school in 2014. For Wang, the experiences she gained from her background as a woman in the male-dominated field of engineering have helped her be a better leader in her role now. The ways she was supported by colleagues who understood specific pressures she experienced make her a more understanding leader, she said.

“It's my turn to make sure my colleagues get that support,” said Wang.

Of the 15 colleges and universities in Central Massachusetts, Wang is one of three female presidents, along with Nancy Niemi of Framingham State University and Mary Lou Retelle of Anna Maria College in Paxton.

“College presidents are so visible, and visibility is so important,” said Jean Beaupre, dean of the school of business and associate professor at Nichols College in Dudley. College presidents are face-out for students, faculty and leadership, and externally.

The role women leaders play

Female presidents are poised to contribute to college and universities beyond offering that inspiration and representation, especially as the industry transitions over the next few years, said Beaupre.

“Womens’ leadership traits and diverse perspectives are characterized by ethics and fairness, collaboration, and openness to change,” said Beaupre.

That disposition will be necessary to confront the challenges of a tight labor market, she said. The other part of the need to push for female presidents is because it's important for college leadership to reflect the makup of its student body, said Beaupre.

“It's important to have leadership that reflects the audience it serves,” she said.

Colleges are at a critical juncture, said Wang, and many are adjusting their focus as the skills employers require of graduates are changing.

“We are revitalizing STEM education to meet workforce needs,” she said.

Women leaders are best suited to lead that charge broadly, in higher education and in the corporate world, Silbert said.

“Women leaders are very well poised to take us into the next era of the workplace,” Silbert said.

It’s important, too, that women have a voice as the working world changes.

“Post-pandemic, so many women's roles have been challenged,” she said.

The vision of diversity perspectives can’t be singularly focused, however, said Silbert.

“It's critical to have diverse perspectives leading these schools, not just women,” she said.

Improving the lack of diversity

Gender diversity among college presidents in Massachusetts remains significantly higher than racial diversity, according to the Eos report. At 32%, less than a third of college presidents are people of color, and 16.5% of college presidents are women of color. That figure is up a significant amount in the last five years: In 2018, only 6% of Mass. college presidents were women of color. There has never been a female Hispanic college president in Massachusetts.

Central Massachusetts has four people of color, or 27%, leading colleges and universities, and one is a woman (Wang).

It’s unconscious bias that gatekeeps these leadership roles from women and non-white applicants, said Silbert. There is a notion, she said, that CEOs and presidents hold the keys to power, and intrinsic bias leads decision-makers to rule women out for those powerhouse positions at the top of the ladder.

“You hear people say terms like, ‘She doesn't have executive presence.’ What does it mean?” said Silbert. “Or lacking gravitas. We hear that all the time.”

A solution, she said, is to bring objectivity into decision making and keep subjective factors and indefinable terms out of the process.

“Objectivity works well for underrepresented groups,” said Silbert. “Cast a wide net, de-bias the process, and don't stop the work with the finalist pool.”

Bringing women into leadership roles is a forward-looking step, said Beaupre. It’s one that will play a part in preparing students for a rapidly changing work environment.

“We are preparing students now for jobs that don't even exist,” Beaupre said.

Historical and systemic issues brought the higher education industry to a point of inequality among top leadership, and strides are being made to continue changes. For Wang, an inside-out approach is what she as a leader can do now.

“It's our turn to make sure we support students, faculty, staff, and continue to push progress,” she said.

0 Comments